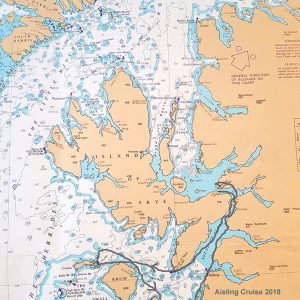

Adrift in Caledonia

Northerly winds dictated the route of our week’s cruise around the Inner Hebrides, so with full sail up on our Contessa 32 we headed south along the rock strewn coasts of Skye. Atlantic gales bring powerful seas and winds to this west facing coast of Scotland so cruising sailors have to be hardy and cautious … some reasons why there are so few.

There’s many variables about west coast sailing but there is one certainty: rain. Often arriving horizontally but then again often innocuously persistent and even pleasantly warm thanks to the Gulf Stream; but frequently never ending. Our cruise had all the classic west coast weather ingredients – two gales, heavy rain, stunningly clear sunshine and thankfully only neap tides.

“You can tell it’s very windy because the rubber dinghy flies behind the boat,” reminisced my chum Ronan whose been flying his dinghy off the stern occasionally for the last 15 years of owning his beautiful Contessa 32.

She was reputedly one of the few yachts to finish the disastrous 1979 Fastnet Race. Her main features are a thick keel-stepped mast, deep semi-long keel and near 50% ballast ratio. While not being weirdly shaped like other old IOR wannabes her designer Jeremy Rodgers instead created a simply beautiful and fast cruiser-racer.

So, a well equipped vessel for the dreaded Minch, one of the stormiest waterways in Europe that lies between the Inner and Outer Hebrides. As a child I’d crossed it on family holidays and watched in amusement as passengers’ hats flew off into the Minch from the Calmac ferry, fluttering among the gannets that streaked past in the stiff breeze.

On our Contessa, as we approached it from along the south coast of Skye after the ebb tide had pushed us through the Kylerhea Narrows we tucked a reef in; just in case. Passing the MacDonald stronghold at Armadale Castle that is now the world famous Clan Donald cultural Centre, we discussed the two rival clans that ran Skye, the MacDonalds and the infamous MacCleods. They often crossed claymores once the Vikings had retreated.

Descended from them, the early MacDonalds were part of the famous Lord of the Isles dynasty that ruled, mostly after the Vikings left in the 13th century. The island played many parts in history, including being the home of Flora MacDonald who took the defeated Prince Charles Edward Stuart over to Skye after Scotland’s final major defeat to the English at Culloden in 1746.

As a child with my grandad we’d once stayed in the Royal Hotel in the island’s capital of Portree while searching for my great granny’s family and recalled how that very hotel had also sheltered the Prince. Flora and the largely Highland army were to suffer more afterwards in what became the dismantling of Highland culture and the clan system.

The wearing of the plaid was banned, as was the playing of the pipes but worst of all was the outlawing of our language, the Gaelic. So despite growing up in a Gaelic speaking household I was not encouraged to speak the language.

Ring of Bright Water

History lies heavily in the Highlands but there is plenty of it to choose from, as we’d found out at our first anchorage the night before. Sailing into the mainland bay of Sandaig we visited the former home of Ring of Bright Water author Gavin Maxwell. The colourful aristocrat had leased a house here and used the burn for his beloved otters.

However, before his epiphany to wildlife saviour he’d decimated the local basking shark population; which has never recovered. Looking west from Sandaig the stupendous views encompassed a horizon filled with islands – the Small Isles – that we now had the sleek bows of Aisling pointed at.

Shelter is never far on the west coast, thanks to the large majority of Scotland’s nearly 800 islands being on this seaboard. The Stornoway Coastguard VHF forecast warned of westerly gales so we were heading for an anchorage to ride them out, on the low lying island of Canna; described in the Clyde Cruising Club’s Sailing Directions as an excellent anchorage and sheltered from all directions. Obscuring it was the brooding mountains of Rum and dotted around its shores could be seen fish farms; one of the modern success stories of this region.

Looking to our east the towering peaks of the Cuillins, some of the highest mountains on the west coast jutted out from Skye. A few turns were put in the big genoa as we rounded the north point of Rum and saw another reminder of the weather – the 2011 wreck of a large French stern trawler, the Jack Abry II looking as if it was berthed against the high cliffs.

The green and verdant Canna lay low and its wide bay looked welcoming as we glided in. A grey seal swam over and snorted at us while a flock of geese honked overhead. Also welcoming was the 10 government supplied moorings which were plentiful, despite four other yachts being there already.

Stillness descended on this haven as we sat in the cockpit, celebrating with a dram from Skye’s Talisker distillery. Surrounded by land I studied the few buildings: the nearby small stone church, the farm steading, and on the smaller island of Sanday a grand neo-Romanesque church.

This was now the archives for Gaelic writing, established by the benevolent last owner, John Lorne Campbell, before he gave the island to the National Trust. It helps having friends with connections, so my mate Ronan being a well known and travelled musician knew many people among the isles, including the famous singer Fiona J. Mackenzie who we visited the next day in the Campbell’s grand house. Fiona told us about her archival work and the struggle since the 2017 closure of the school that reduced island numbers to only 14 people.

Vikings and priests

Waves of history passed through this arable land including religious proselytisers who displaced the druids of the Pictish nation with St Columba’s Catholic priests in the seventh century. After the Norsemen slaughtered them, longships were berthed here for 500 years but their remains have been often elusive to find.

However, modern lasers and aerial radiography is revealing much, such as the 2017 find of a Viking boatyard across the water in western Skye. Today Canna remains Catholic but has a protestant church dating from 1914, as well a new style accommodation for backpackers; small huts called ‘pods’ that have proliferated throughout the Highlands recently.

Aboard Aisling we sheltered from the rain under the cockpit tent then ate our sausage hotpot snug beside the diesel heater as the force seven westerly gale hit; the horizontal rain even drove the herd of Highland cattle in the rowan trees for shelter.

A day later, with full sail the 2,500ft peaks of Rum loomed over us. Named in Gaelic as mountain of the troll (Trollaval), the middle peak alluded to the island’s dark history. Like many Scottish islands, Rum had suffered at the hands of eccentric foreign owners who removed many people during the dark times of the 19th century Highland Clearances and then used the island as a play park.

The last of these rogues was Sir George Bulloch who spent three weeks annually on Rum after building the stately home of Kinloch Castle and filling it with exotic artefacts. As we passed the island’s dark and empty landscape, with only the rubble of houses left, it told its own sad story. Bought back by the Scottish government in the 1957, wildlife is now the main benefactor of this wasteland that was once a homeland. We saw sea eagles gliding past and my binoculars picked out deer near the tree line just above the main anchorage at Loch Scresort.

Well heeled over, Aisling felt the full force of the Atlantic south of Rum as we neared the lower lying Eigg, its Sgurr (meaning ‘buck tooth’ in Gaelic) giving it the shape of an upturned fin keeler. The basalt rocky Sgurr towers over arable fields sheltered by copses and as we rounded the south east corner the small haven of Galmisdale came into view.

With yet another gale on the way, this slightly exposed anchorage was only possible for us because a fellow Contessa 32 owner Simon was lending us his mooring for the night. After skimming over the shallow sandy bottom that lay between an islet and the main island I grabbed the floating warp to secure us. Launching the Avon dinghy and stemming the fast flowing tide that ran through, we eventually reached the slipway to start our exploration.

We considered seeking out the famous Massacre Cave where the MacCleods had burned all the islanders and talk grew maudlin as we discussed how the MacCleod’s ascendency was assured after fighting on the winning English side in the battle of Culloden, until we’d become very glum and in need of a dram.

So we sought the Laig brewery which was run by Ronan’s mate Gabe. Ronan had brought his fiddle ashore so we were keen to have a ceilidh. Perched high on the island, the view from Gabe’s brewhouse showed the mainland peninsula of Scotland’s most westerly point at Ardnamurchan and to our north the Outer Hebrides. These islands included Lewis, the birthplace of yet another infamous MacCleod; Mary-Anne, the mother of US President Donald Trump.

Ceilidh

Despite being busy brewing for what he said was an exceptionally busy tourist season fiddler Gabe agreed to meet us at the island pub later for a session. So, with clanking beer filled rucksacks we wound our way down the island calling in at a few of the 70 residents to let them know about the ceilidh. Ronan had gone to high school in Portree with many of them so it was familiar welcomes in Gaelic and English.

Eigg is world famous for its community buyout, from what was yet another rogue landlord in 1997 and has been studied by international organisations as a model of sustainability. It now is also self-sufficient in electricity thanks to solar and wind turbines. But it relies on a vibrant community of multi-skilled people including many English folk escaping the congested south; so a much friendlier invasion force than in 1746.

A recent lifeline is the pier for the Calmac ro-ro ferry (despite visiting cars being forbidden) which allows produce and equipment to be landed easily. While having a few beers at the ceilidh with Dean from Wolverhampton he told me how he decided to paddle his kayak over to the island. Cold and near penniless, he was given clothes and shelter.

“That was 10 years ago and I’ve been here ever since!” Dean reflected.

Another English couple were sailing past in their bilge keeled Maurice Griffiths Golden Hind and followed the same happy fate. At this juncture, I should warn readers that this lifestyle involves a lot of self-sufficiency and surviving a Highland winter is indeed a badge of honour; something I can vouch for having been born in the most northerly village in the British Isles.

Back at the anchorage the wave caps were white like my knuckles during our midnight dinghy ride.

“One mistake and we’re across the Minch to Mallaig!” warned a merry Ronan who jealously guarded his fiddle case from the spray.

That wild night, Aisling bucked like a Highland coo covered in midges. I lay spread-eagled in the fo’c’lse but 6ft 3ins Ronan wasn’t so lucky in the small saloon berth, that tossed him onto the cabin sole.

Over the sea to Skye

The following day the mighty Sgurr of Eigg was our back-bearing during a roller coaster broad reach across the Minch and then the calmer Sound of Sleat to the busiest fishing town on the west coast: Mallaig.

“Geewhiz there’s traffic lights at the entrance!” I shouted back to Ronan from the bow as we dodged a fast moving Calmac ferry Skye-bound.

It was only about six years ago the fisherfolk of Mallaig relented to let us pesky yachties share their busy port, so now before us lay the most northerly marina on the west coast; but still exposed to the east (in case your thinking of wintering here).

Yet more civilisation awaited in the form of the French style boulangerie and lots of what I call tartan-trock shops clustered around the station where the Hogwarts steam express from Glasgow was decanting Harry Potter fans. Ducking into the nearby Fisherman’s Mission to escape the throng we had the best haddock and chips in years.

As is the west coast way, the weather changed to solid rain by then so a sprint to the nearest hostelry brought us to the Marine Bar, where another surprise awaited us on the muted television; a glum looking Malcolm Turnbull.

“Yep we’ve changed again so let’s see … that’s our seventh prime minister in only 11 years,” I replied to the burly barman’s questions. We agreed west coast weather and Australian politics had something in common.

Yet our stroll back to the marina for what was the last night of our voyage rewarded us with a dramatic sunset of towering clouds and butterscotch light over the mighty Cuillins Mountains. As writer Gavin Maxwell quite rightly said, many things may change but the rocks remain.

Navigation

Charts – we used Navionics on our plotter and phones

Sailing Directions – The Clyde Cruising Yacht Club Guide (include Gaelic place name translation) available from <www.clyde.org>

Sailing guide book – the excellent Scottish Islands and by experienced sailor Hamish Haswell-Smith

Cruising Guide – Welcome Anchorages 2018 www.yachtinglife.co.uk

Weather – Stornoway Coastguard on VHF Channel 10

Tides – Navionics or local guides. Tides vary from 2m-4m

Marina Services – only at Mallaig with limited supplies on the Isle of Skye.

Anchorages – many including at the capital of Skye at Portree (east facing)

Ports – Portree, Mallaig and main haulage port at Uig on the west of Skye.

General Information

Scottish Sailing – www.sailscotland.co.uk

Chartering – Isle of Skye Charters (www.skyeyachts.co.uk) at Armadale Bay South Skye

Travel – trains and buses run from Glasgow and the Highland capital of Inverness to the Skye bridge at Kyle of Lochalsh.

Airports – main international airports are at Glasgow and Edinburgh (with direct flights from Australia)

Seasons – the summer runs from June to August and daylight is until 10pm so this is the best cruising time.

Tourism in general: www.visitscotland.com